Expo

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

Medical Imaging

AICritical Care

Patient CareHealth ITPoint of CareBusiness

Events

- Specialized Face Mask with Gas Sensor Detects Chronic Kidney Disease

- Implantable Device Continuously Monitors Brain Activity in Epileptic Patients

- Mechanosensing-Based Approach Offers Promising Strategy to Treat Cardiovascular Fibrosis

- AI Interpretability Tool for Photographed ECG Images Offers Pixel-Level Precision

- AI-ECG Tools Can Identify Heart Muscle Weakness in Women Before Pregnancy

- Bioprinted Aortas Offer New Hope for Vascular Repair

- Early TAVR Intervention Reduces Cardiovascular Events in Asymptomatic Aortic Stenosis Patients

- New Procedure Found Safe and Effective for Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Mitral Valve Replacement

- No-Touch Vein Harvesting Reduces Graft Failure Risk for Heart Bypass Patients

- DNA Origami Improves Imaging of Dense Pancreatic Tissue for Cancer Detection and Treatment

- First-Of-Its-Kind Portable Germicidal Light Technology Disinfects High-Touch Clinical Surfaces in Seconds

- Surgical Capacity Optimization Solution Helps Hospitals Boost OR Utilization

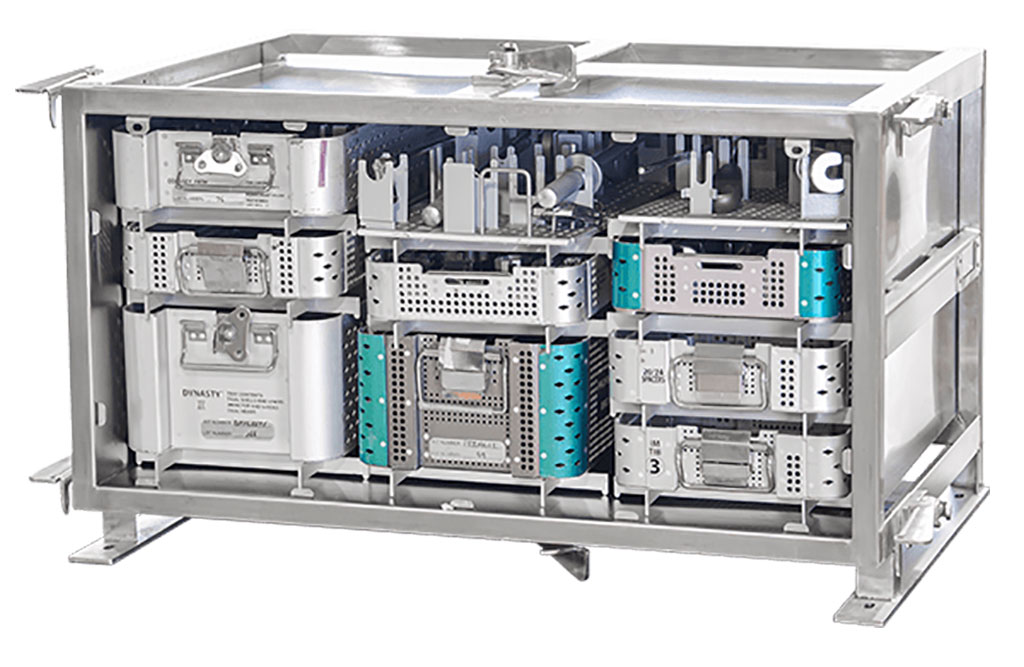

- Game-Changing Innovation in Surgical Instrument Sterilization Significantly Improves OR Throughput

- Next Gen ICU Bed to Help Address Complex Critical Care Needs

- Groundbreaking AI-Powered UV-C Disinfection Technology Redefines Infection Control Landscape

- Becton Dickinson to Spin Out Biosciences and Diagnostic Solutions Business

- Boston Scientific Acquires Medical Device Company SoniVie

- 2026 World Hospital Congress to be Held in Seoul

- Teleflex to Acquire BIOTRONIK’s Vascular Intervention Business

- Philips and Mass General Brigham Collaborate on Improving Patient Care with Live AI-Powered Insights

- Smartwatches Could Detect Congestive Heart Failure

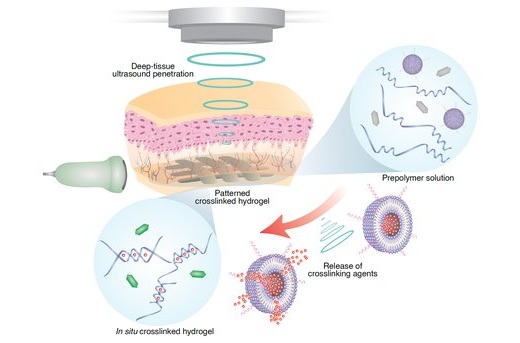

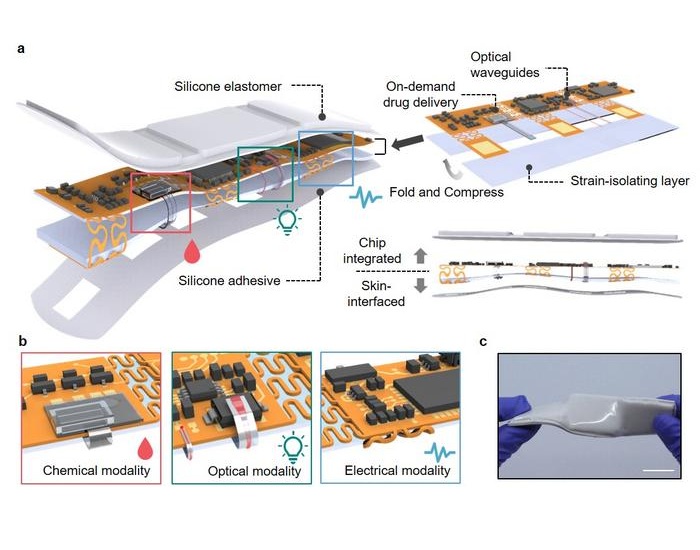

- Versatile Smart Patch Combines Health Monitoring and Drug Delivery

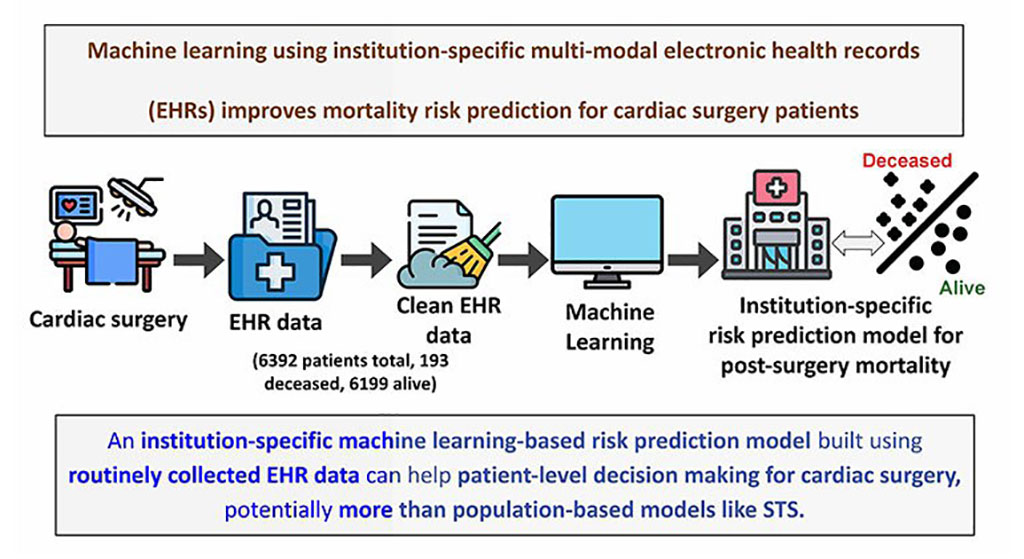

- Machine Learning Model Improves Mortality Risk Prediction for Cardiac Surgery Patients

- Strategic Collaboration to Develop and Integrate Generative AI into Healthcare

- AI-Enabled Operating Rooms Solution Helps Hospitals Maximize Utilization and Unlock Capacity

Expo

Expo

- Specialized Face Mask with Gas Sensor Detects Chronic Kidney Disease

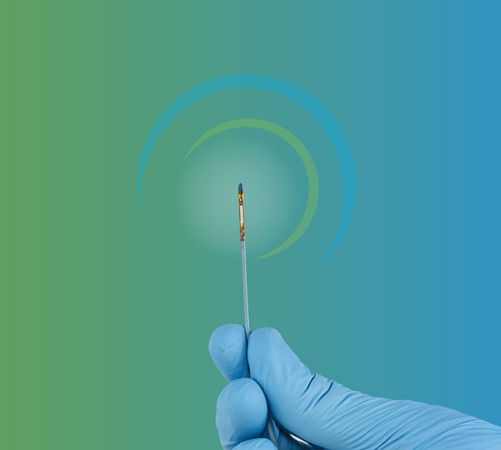

- Implantable Device Continuously Monitors Brain Activity in Epileptic Patients

- Mechanosensing-Based Approach Offers Promising Strategy to Treat Cardiovascular Fibrosis

- AI Interpretability Tool for Photographed ECG Images Offers Pixel-Level Precision

- AI-ECG Tools Can Identify Heart Muscle Weakness in Women Before Pregnancy

- Bioprinted Aortas Offer New Hope for Vascular Repair

- Early TAVR Intervention Reduces Cardiovascular Events in Asymptomatic Aortic Stenosis Patients

- New Procedure Found Safe and Effective for Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Mitral Valve Replacement

- No-Touch Vein Harvesting Reduces Graft Failure Risk for Heart Bypass Patients

- DNA Origami Improves Imaging of Dense Pancreatic Tissue for Cancer Detection and Treatment

- First-Of-Its-Kind Portable Germicidal Light Technology Disinfects High-Touch Clinical Surfaces in Seconds

- Surgical Capacity Optimization Solution Helps Hospitals Boost OR Utilization

- Game-Changing Innovation in Surgical Instrument Sterilization Significantly Improves OR Throughput

- Next Gen ICU Bed to Help Address Complex Critical Care Needs

- Groundbreaking AI-Powered UV-C Disinfection Technology Redefines Infection Control Landscape

- Becton Dickinson to Spin Out Biosciences and Diagnostic Solutions Business

- Boston Scientific Acquires Medical Device Company SoniVie

- 2026 World Hospital Congress to be Held in Seoul

- Teleflex to Acquire BIOTRONIK’s Vascular Intervention Business

- Philips and Mass General Brigham Collaborate on Improving Patient Care with Live AI-Powered Insights

- Smartwatches Could Detect Congestive Heart Failure

- Versatile Smart Patch Combines Health Monitoring and Drug Delivery

- Machine Learning Model Improves Mortality Risk Prediction for Cardiac Surgery Patients

- Strategic Collaboration to Develop and Integrate Generative AI into Healthcare

- AI-Enabled Operating Rooms Solution Helps Hospitals Maximize Utilization and Unlock Capacity